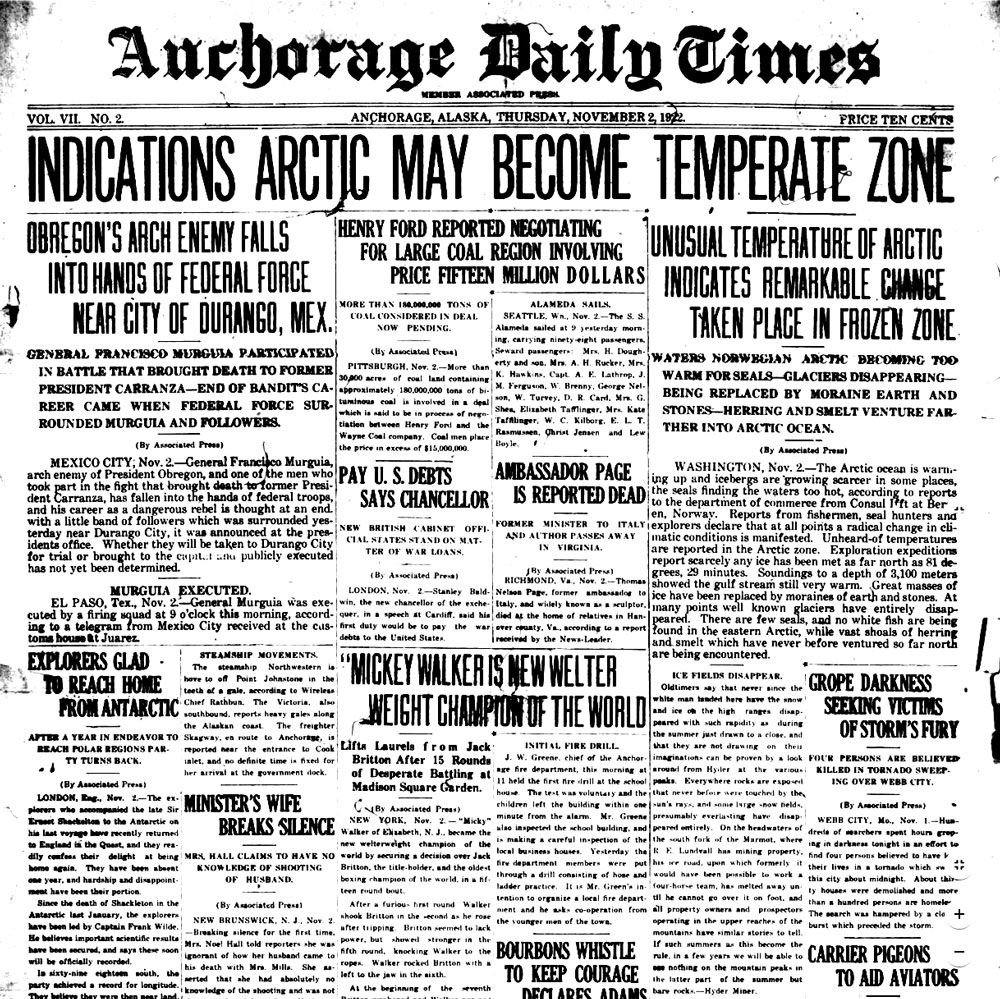

Photo Source: James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal

"Restoring A Great Intellectual Tradition To America’s Campuses."

Article by George Leef, August 16, 2019, James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal

"Americans used to relish good debates.

The debates between Senator Stephen Douglas and his challenger Abraham Lincoln in 1858 were transcribed and widely read. Even though Lincoln lost the election, the quality of his arguments impressed so many people that he became the Republican Party’s nominee for president just two years later.

College campuses are a natural venue for debates over the full range of political, economic, and philosophical issues that face us. Colleges have (or at least should have) a commitment to inquiry and the free exchange of ideas. And seeing how adults who have prepared for the intellectual combat of debate handle themselves is an important aspect of the preparation for citizenship that’s part of higher education’s mission.

Unfortunately, debate has largely disappeared on most campuses. That is the finding of political science professor George La Noue in his book Silenced Stages: The Loss of Academic Freedom and Campus Policy Debates.

Based on his study of 97 colleges and 28 law schools during the 2014-2015 academic year, La Noue concludes,

“For most students in American higher education, the opportunity to hear on-campus debates about important public policy issues does not exist.”

It isn’t the case that policy debates have completely disappeared. Sometimes colleges host debates over environmental and health issues, but such crucial matters as gun control, affirmative action, free speech, sexual assault, international trade, abortion, and government finance were almost never debated on campus during that period. La Noue is interested in the reasons for the decline of debate.

One of if not the main reason why is that many students and even academic leaders now subscribe to the idea that some ideas are simply beyond discussion and must be “deplatformed.”

Of course, those are ideas they happen to disagree with, and their banishment is often accomplished by calling it “hate speech.”

To advocate immigration restrictions, for example, is to engage in hate speech according to the president of the University of Maryland. Such speech, he declares, does not enjoy any protection under the First Amendment—even though the Supreme Court has never accepted any distinction between “hate speech” and pure speech.

Politically aggressive students often take the lead in opposing speakers (whether they’re participating in a debate or not) who will presumably say things that make some students feel uncomfortable or even 'unsafe.'

La Noue cites the case of Williams College, where a black liberal student named Zack Wood wanted to stimulate robust discussion on campus by inviting speakers who argue in favor of controversial positions.

When he invited Suzanne Venker, a critic of feminist orthodoxy, he encountered strong opposition. Among the responses was this one:

When you bring a misogynistic, white supremacist men’s rights activist to campus in the name of 'dialogue' and 'the other side,' you are not only causing actual mental, social, psychological and physical harm to students, but you are also—paying—for the continued dispersal of violent ideologies that kill and harm black and brown (trans) sisters …you are dipping your hands in their blood, Zach Wood.

That intemperate blast underscores the problem facing free speech advocates. Many students are so certain that people they identify as being on 'the wrong side' are evil that they must be prevented from speaking to avoid all the alleged harm they’ll cause.

Those students don’t have to listen to the individual and evaluate his message; they just know that nothing the person might say has intellectual value. That mindset prevents people from receiving ideas that challenge the belief system of the speech policers.

Debate [then] is shut down.

Lest any reader think that the hostility to debate and other forms of communication is a minor problem that has happened only a few times, La Noue provides many examples.

They include the riot at Middlebury College that forced Charles Murray and professor Allison Stanger to flee from a violent mob and the petition at Vanderbilt demanding that professor Carol Swain be fired for having said something critical of Islam after the Charlie Hebdo murders in Paris.

Perhaps the most shocking is the way law students tried to prevent professor Josh Blackman from giving a talk about the importance of freedom of speech. When future lawyers have absorbed the idea that it’s appropriate to block people from speaking rather than countering arguments they make that you find unpersuasive, our society is in deep trouble.

And perhaps we are in deep trouble quite aside from the problem of future lawyers who don’t believe in listening to arguments they’re sure they’ll dislike. From opinion polls La Noue cites and the behavior of many undergraduates, it’s apparent that many young Americans don’t much support the First Amendment.

They’re fine with restraints on speech to avoid hurt feelings and don’t see that the search for truth gets sidetracked when people act like warring tribe members rather than rational beings. Some buy into the notion that truth is subjective and therefore argument is pointless. Those are perverse notions that must be countered.

Thankfully, at least a few higher education leaders agree that we face a problem. La Noue quotes Donald Farish, president of Roger Williams University, who writes:

'If college campuses are being targeted as battlegrounds between extremists on the left and right, then college presidents have to find ways to reclaim the middle ground. This starts with conversations between the institution’s administration and campus political groups and the creation of forums for debate between representative voices from left and right. A true debate, where students are invited to witness a meaningful presentation of opposing views, is far more interesting and useful than one-sided diatribes.'

Farish is right, but preparation for such debates should begin at the start of each student’s college career.

As part of orientation for new students, colleges ought to emphasize that intellectual progress has always depended on the exchange of arguments and counter-arguments; that the only proper approach to such exchanges is to respectfully listen and think—never to heckle, ridicule, demean, shout down or assault a debater. Students need to be reminded that no one was ever persuaded to believe in an idea because of disruptions, name-calling, or physical threats.

I would suggest that before having any actual debates, students should have to watch a recorded debate on a topic of current interest so they can observe how good advocates conduct themselves and how an audience properly behaves.

An excellent source in that regard is the SoHo Forum, which regularly hosts debates such as this one on the merits of socialism versus capitalism.

Professor La Noue hits the nail squarely on its head when he writes,

'Opening up spaces for different ideas can be pursued by sponsoring on-campus debates and forums about important policy issues. That action will send a message to groups that when offended they do not have the right to suppress speech they do not like.

Moreover, debates can create recognition and a space for dissenting ideas that will enrich classroom discussions, research agendas, and hiring decisions Policy debates can function like tilling exhausted soil so that new life can grow.'

Everyone involved in the enterprise of higher education should read Silenced Stages and take its message to heart." - George Leef

George Leef is the director of editorial content at the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal.

Above article by George Leef, August 16, 2019, James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal